From Diego Rivera’s Paintings to the Fields of California

Text and Photographs by David Bacon

Dollars and Sense, January/February 2023

https://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2023/0123bacon.html

Along West Ocean Avenue in the summer of 2022, where Lompoc, California’s flower fields meet the edge of town, workers from Oaxaca and Guerrero were harvesting stock flowers. Even far from the rows where they labored, breezes carried the overpowering, almost sickly-sweet fragrance from thousands of blooms.

Stock flowers often anchor elaborate floral arrangements at funerals, their familiar smell calling up memories of churches and death. In Mexico, where Day of the Dead displays always feature brilliant orange marigolds, a family that has lost a child sometimes substitutes white stock blossoms on their altar. For them, the scent and color exercise a singular power to awaken memories of lost innocence.

Workers in the Lompoc field were harvesting stock flowers in several colors-white for funerals, as well as deep purple, pale yellow, violet, and an orangey rose. As each worker moved down a row, he’d pull up a plant, roots and all. Gathering together half a dozen stalks, he’d reach for one of the paper-covered wire ties hanging from his belt. Wrapping the tie around the stems, he’d spin the bunch of flowers like a propeller, twisting it tight and banding them together.

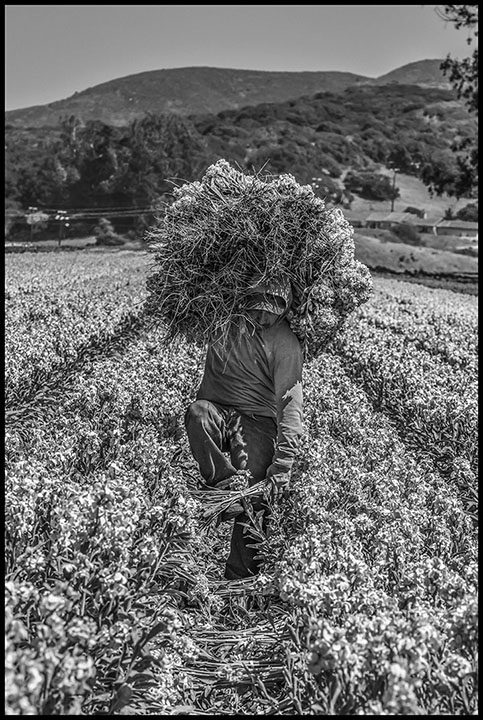

As each worker went down the field, he’d leave a trail of tied bunches behind him. Then, after harvesting enough, he’d move back up the row to collect them. With his foot he’d lever each bunch into his outstretched hand, and then throw it backwards, on top of a growing pile of flowers on his shoulders. At the end of the row his face would be virtually hidden behind hundreds of stems and blooms.

Carrying this load, the worker would arrive at a truck, and carefully lay the pile of fragrant flowers on the grass and dirt. Once one of the two flower knives was free, he’d use its guillotine-like blade to cut off the roots, and bunch by bunch pack the stalks into a plastic bucket. His last act would be to hoist the bucket up to the loader, stacking hundreds in the back of a waiting trailer.

Diego Rivera’s 1935 painting “The Flower Carrier,” one of his best-known canvasses, shows a man bent down by the weight of a pile of flowers on his shoulders. It is the centerpiece of the Rivera collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and was the highlight of its recent show of the revolutionary muralist’s smaller works.

Eighty-seven years have elapsed between its creation and last year’s flower harvest in Lompoc. But there is more than a coincidental similarity between Rivera’s image of the man bent beneath a huge bunch of purple flowers, and a photograph of a man carrying a similar burden in a California field. Is the 1935 flower carrier connected in some way to today’s flower harvesters? The images provoke questions. What happened to the flower workers of Rivera’s era? Did the social commentary he deftly integrated into the painting in some way predict their fate?

The man in the painting looks not unlike the workers in the Lompoc field. His pile is made up of beautiful purple blooms in a huge tight bunch, more like dahlias or zinnias than the stalky stock. But the painted sensation of weight feels the same as that felt in a photograph of a half-bent worker at the end of a row.

Like the painted figures of the man and the woman helping him to rise under his load, most workers in the Lompoc rows are short and dark-skinned. That similarity is even more pronounced in Rivera’s 1926 painting of the “Flower Seller” (also part of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art show)-which shows a woman with a basket of flowers in front of her. Rivera paints an explicitly indigenous woman, facing the viewer. Her indigenous identity is clear, as is that of the Lompoc workers, a crew made up of migrants from the Mixtec and Triqui communities of Oaxaca.

According to art historian John Lear, Rivera’s model for “The Flower Seller” was Luz Jimenez, a Nahuatl woman who posed for him many times. The painting gives her a specific personality, through her forthright gaze. While the painting just shows her selling the flowers, they seem to be ones she might have grown as well. Mexico’s new post-revolution culture, through Rivera’s depiction, views indigenous people as the true Mexicans, countering the earlier colonialist stereotypes elevating European ancestry, while treating Mexico’s original inhabitants as ignorant savages.

By 1935, however, the tone of Rivera’s painting has changed. The “Flower Carrier” has no specific identity. He and the woman helping him seem to be the campesinos who have grown the flowers, but the flowers have become a burden, as beautiful as the blooms might be. And if they’ve grown them, they don’t seem to be expecting a transformation of their lives because of this labor.

Yet that was the promise of the Mexican Revolution in the early 1900s. Land reform and a political commitment to a socialist or egalitarian future, and especially support for rural indigenous communities, would provide a life with dignity, free from exploitation, or at least with less of it. Rivera’s flower carrier is not celebrating this future, however. Instead, the painting raises doubts about where it’s all heading.

Rivera’s flower workers are farmers, producers of what they sell. They are not rural wage workers, much less migrants who labor in industrial flower production. Yet even as Rivera painted his campesinos, people from Mexico’s countryside were already being displaced. A post-revolutionary wave of migration had already arrived in California and the southwest in the 1910s and 1920s. By the 1930s, when he painted the “Flower Carrier,” a wave of anti-immigrant hysteria in the United States had already led to the mass deportation of tens of thousands of migrants, sending them on a return trip to Mexico.

Rivera was not ignorant of this. In one watercolor from 1931, “Repatriated Mexicans in Torreón,” which was painted three years before “The Flower Carrier,” he shows migrants returning to Mexico after being swept up in those raids.

According to Lear, “While he was in Detroit [painting his famous murals of auto assembly plants], Rivera became the founder, funder, and leader of the 5,000-member Liga de Obreros y Campesinos, whose primary goals, shared with the Mexican consul, were to find local work for, or support the voluntary repatriation of, unemployed Mexicans.”

In those years, however, tens of thousands of Mexicans, and even their U.S.-citizen children, were not repatriated voluntarily at all. They were simply loaded onto boxcars and shipped to the border.

Rivera’s engagement with farmworkers, as opposed to industrial workers, was much less direct. During the same visit to the United States he painted a fresco, “Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees,” in the home of Sigmund Stern in the wealthy enclave of Atherton, on the San Francisco Peninsula. In it Mexican-appearing laborers are hoeing in an orchard, while another man drives a tractor behind them. The work seems hard, although not excessively so. But the painting shows no inkling of the rebellion that was about to take place. In 1932, tens of thousands of farmworkers, a majority Mexican, mounted the largest agricultural strike in California’s history, the Pixley cotton strike. It was led by the radicals and Communists who were the greatest admirers of Rivera’s work. Some, like his assistant of that period, Emmy Lou Packard, went on herself to produce beautiful lithographs of working farm laborers.

In Mexico, things had not worked out as the revolutionaries of the 1910s and 1920s had hoped. The revolution’s changes slowed and eventually stalled, making life as an independent farmer in rural Mexico untenable, while the migrant labor of displaced Mexican campesinos became indispensable to the growth and profits of industrial agriculture in California. Eventually, Mexican farmers’ displacement and Californian landowners’ hunger for labor created the flower workers of Lompoc. The trajectory between Rivera’s paintings and the photographs in California’s fields traces visually the social transformation of the people who were once Rivera’s subjects, and then became migrants cutting flowers 2,000 miles away, a border and almost a century apart.

In Mexico’s countryside, by 1970 over 70% of small farmers could not live on the crops they were able to grow, or what they were able to earn by selling them, as Rivera’s flower sellers must do. From 1950 to 1976 Mexico’s population doubled, and the number of people living on each square kilometer of farmland did also, from 36 to 67. By then two-thirds of rural families couldn’t afford to eat meat most weeks. Mexico City’s growth couldn’t provide jobs for all those coming in from rural indigenous communities. Migration north to the maquiladora cities of the border, and across the border into U.S. fields, was increasingly the answer for survival.

According to the late Rufino Dominguez, one of the founders of the Frente Indigena de Organizaciones Binacionales, about 500,000 indigenous people from Oaxaca lived in the United States by 2000, 300,000 in California alone. Many came from communities whose economies are totally dependent on migration. The ability to send a son or daughter across the border to the north, to work and send back money, makes the difference between eating chicken or eating salt and tortillas. Migration means not having to cut furrows in dry soil for a corn crop that can’t be sold for what it costs to grow it. It means that dollars arrive in the mail when kids need shoes to go to school, or when a grandparent needs a doctor.

Mexico’s National Council of Population reported in the Census of 2000 that in Oaxaca 12.5% of people lived with no electricity, 26.9% lived in homes with no running water, and children got an average of 6.9 years of school. The displacement of people from Oaxacan communities tracks with the growth in poverty. By 2000, 18% of Oaxaca’s people had left for other parts of Mexico and the United States. As a result, according to the Indigenous Farmworker Study, one-third of the 700,000 farm workers in California come from Oaxaca and other states in southern Mexico. Of all farm workers in California, indigenous workers receive the lowest pay. According to the study’s author, Rick Mines, one-third reported earning the minimum wage, and an additional one-third reported earning less than the minimum-a wage that violates California state law. Most indigenous families live in crowded conditions in apartments or trailers. In some areas the most recent arrivals live outside in tents-even under trees.

But despite bad housing, low wages, and discrimination in the United States, migration is not just the preferable, but sometimes the only recourse for ensuring survival. “There are no jobs in Oaxaca, and NAFTA [the North American Free Trade Agreement] made the price of corn so low that it’s not economically possible to plant a crop anymore,” Dominguez asserted in an interview in 2008. “We come to the U.S. to work because we can’t get a price for our product at home. There’s no alternative.”

By 2010, 49.3% of Mexicans lived in poverty, an increase of 6 million people in the previous two years of economic recession, according to estimates from the Economy and Business Investigation Center of the Monterey Technology Institute for Higher Studies. The year of 2008 marked the peak in Mexican migration during the quarter century after NAFTA went into effect, in which the number of Mexican migrants in the United States rose from 4.6 to 12.6 million.

These photographs document the work of Mexican campesinos who are part of that wave of migration, migrants who had to leave Mexico for their families to survive. They’ve become wage workers in industrial flower production, part of the U.S. working class that Rivera admired. In the Lompoc photographs the flower workers are all men. In many crops in California agriculture, including this one, single men dominate migrant labor in the fields. This is especially true today, when the H-2A contract labor visa program last year alone allowed growers to recruit 317,000 people, almost all rural Mexican farmers, to work here. It is a repeat of what happened in the 1950s, when the exploitative Bracero program brought hundreds of thousands of workers from a previous generation into U.S. fields every year.

Rivera’s images treat flower growing and selling as a family operation. Now it is wage work performed by hired hands on industrial-scale farms far from the workers’ original homes. The system of modern migration has put a tremendous burden on many Mexican families, with mostly men leaving, and then sending money home to those left behind. The H-2A program escalates this, even allowing growers to refuse jobs to women, the old, or anyone who can’t keep up with the fierce pace of production.

The workers in the fields in Lompoc, working at that rapid pace, use a unique coordination of body movements to keep up. The skill takes weeks of experience to acquire, and those who can’t or don’t get it quickly find themselves looking for another job. Harvesting flowers is exhausting but takes such skill and strength that it’s obvious to workers that what they do is essential, and that not everyone can, or is willing, to do it. In the field next to the flowers, another crew walks to the road after harvesting celery all day. Here the workers who have been packing the vegetables are women. Their rubber aprons flap in the wind as they stride confidently down the rows. Neither the flower nor the celery crew looks ground down by the labor. They may no longer be farmers on their own land, but they work and walk with the assurance of the skilled wage earners they’ve become.

David Bacon is a California-based writer and photographer. He is the author of several books about migration. His latest book, More Than a Wall/Mas que un Muro, was just published by the Colegio de la Frontera Norte (Tijuana). He was a factory worker and union organizer for two decades, and has been documenting the lives of migrants and farm workers through photographs and journalism since 1986.

Leave a Reply