By David Bacon

The Nation, 3/6/23

https://www.thenation.com/article/society/across-the-tracks/

The tracks divide downtown from west Fresno, and a man crosses as the rain begins.

In the San Joaquin Valley, the most productive agricultural area in the world, poverty is endemic. Fresno, crisscrossed by irrigation canals and railroad tracks, is the working-class capital and largest city of California’s San Joaquin Valley, a city where people speak Spanish as readily as English. Here the polarization of rich and poor is a constant theme in its history, and the story of its present. The banks and growers of the valley built ornate office buildings and movie palaces when the downtown was their showplace. Now, as developers abandoned it for the suburbs, the theater entrances and building doorways have become sleeping spaces, refuges from the rain for those with no fixed home.

Crossing the tracks to the neighborhood where many of the unhoused people in Fresno live.

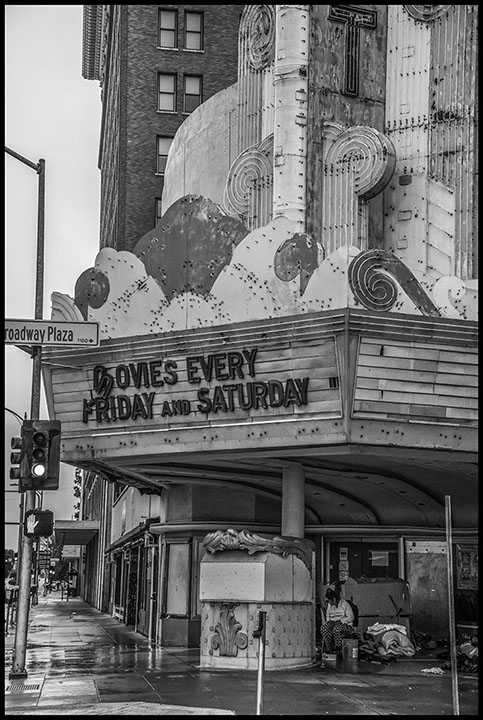

Fresno has one of the oldest Mexican barrios in a state where the Mexican presence goes back decades. Here the abandonment is visible in closed theaters and dancehalls, leaving their marquee as evidence while small tacquerias try to survive. Today the street in front of the Azteca Theater is hauntingly empty at night, but older residents remember when Cesar Chavez and a column of grape strikers stopped in front on F Street in 1966. The strikers were marching from Delano to Sacramento, and hundreds turned out to hear Chavez speak in the street outside. Bisecting downtown are the railroad tracks and the old Highway 99, a defining geography for the settlements of unhoused people. Here community activists and the homeless themselves have pressured a normally-intransigent city government to provide at least enough housing to keep the dream of life off the streets alive. In 2019 Fresno had a larger percentage of “unsheltered” homeless people than any other city in the country – that is, people sleeping on sidewalks, in cars or in places the government calls “not suitable for human habitation.”

Through the Community Alliance newspaper, Mike Rhodes has been one of the most vocal opponents of the campaign by police and sherriffs to drive unhoused people from Fresno.

People try to survive no matter their circumstances. In Fresno they often win community support as they fight for living space in a hard, bare-knuckle city. Mike Rhodes co-founded Community Alliance, one of California’s longest-lived community newspapers in California, and spent 18 years denouncing the city for its abuse of homeless people. Rhodes’ book, Dispatches from the War Zone, recounts the many efforts for years by the city to drive encampments off the streets, and the community’s resistance. At one point he asked the city manager, “With about a thousand homeless people in the downtown area, and inadequate shelter space available, what is the city going to do with people who are homeless?” With no answer about where people should go, Lisa Apper, with the Saint Benedict Catholic Worker, stood in front of the garbage trucks where people’s possessions would have been thrown, saying, “We have got to take a stand for justice.”

The theater showed movies every weekend, and after it closed the entrance became a shelter to sleep out of the rain.

In the latest Community Alliance, Bob McCloskey reports that city Homeless Assistance and Response Teams “relentlessly push [people] daily to move on with no place to go.” The City Council turned down a proposal to allow people living on sidewalks in freezing temperatures to seek shelter in the city Convention Center. Gloria Wyatt told council members, “I am not used to being homeless, but I cannot cover rent. Our tent was torn down this morning, and we have no place to go. I am scared.” The new Mexicans in Fresno are indigenous migrants from Oaxaca and the south, as poor as their migrant predecessors, but who bring with them the cultures and celebrations of their home towns. Rufino Dominguez, a Oaxacan migrant with roots in Mexico’s leftwing social movements, started the Organization of Exploited and Oppressed People in Fresno and Madera, and led strikes when he arrived in the 1980s. For Dominguez, a leader in the Oaxacan community until his death in 2017, keeping indigenous culture alive has been a means to survive.

This Mixtec boy was born in Fresno, and his mother brings him to the celebration of her hometown in Oaxaca.

“Beyond organizing and teaching our rights,” he said in an interview before he died, “we would like to save our language so that it lives and continues. Losing your culture is much easier in the US. We come to the U.S. to work because there’s no alternative. We know the reasons we have to leave. Even though 509 years have passed since the Spanish conquest, we still speak our language and rescuing what we lost in terms of our beliefs.” These photographs recreate an atmosphere of people living in an abandoned downtown, or on the wrong side of the tracks – older residents without homes. Newer residents, lighting votive candles in a garage before going to work, bring a different culture from the south. The images are a reality check, telling a story of poverty and migration. They force acknowledgement of true conditions, and show survival itself as a form of resistance.

Overhead the 99 freeway, the central artery of the San Joaquin Valley, runs next to the tracks, while under it two unhoused people make the journey back from downtown.

Danny Alfiro burns paper in a trash basket to stay warm in a December night.

Along the tracks someone has abandoned a shopping cart with a few belongings.

Larry Collins was an activist living on the streets, and won a living unit when public pressure forced the construction of a small housing complex for unhoused people.

Community activists painted a mural of the faces of people in the downtown barrio.

Joseph and his partner made a home out of the rain in a boarded up downtown doorway.

Hardy’s Theater, built in 1917 in the years when the downtown was the center of Fresno’s life, was abandoned, and its interior destroyed by an evangelical church.

The Chinatown Smoke Shop, in the old barrio.

At night the taco truck stayed open, even at the height of the pandemic, waiting for workers at the Amazon fullfillment center to come by after their shift.

The Tecolote, or Night Owl, dance hall and cafe, in the old strip of clubs, bars and the Azteca Theater.

In a west Fresno garage a Mixtec woman pours atole (Mexican oatmeal) into cups for people coming early in the morning for her hometown’s saints day.

Before leaving for the fields a young farmworker lights a candle to honor St. Michael, the patron saint of his hometown in Oaxaca, San Miguel Cuevas.

In the downtown barrio next to the tracks, the Mexican bus station lists the towns in Mexico people might be returning to, and the towns in Washington State where they might be going to work.

The Mexican bus gets ready to leave, while a mother and her children wait to get on.

Leave a Reply