by David Bacon

Latin American Perspectives, March 2023

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0094582X221149440

David Bacon is a photographer and writer who has documented the social movements on the Mexico/U.S. border for 30 years.. The photographs reproduced here are selected from the book “More Than a Wall/Mas que un muro” published by the Colegio de la Frontera Norte, Tijuana, Mexico, 2022. For more information about the book, write to dbacon@igc.org or click here

Over the past half century the once-small towns of Ciudad Juárez and Tijuana have become cities of millions. A huge part of the industrial workforce in the production and supply chain that delivers products to U.S. consumers lives not on the U.S. but on the Mexican side of the border, where people build homes out of cardboard and shipping pallets cast off by the maquiladoras and the dirt streets of their barrios often end at the border wall.

Many neighborhoods have no sewers and flood when it rains. Electricity is stolen by hooking up to power lines, while drinking water comes in a truck and people must pay to fill the tanks in front of their homes. Often living conditions for poor and homeless people in border cities like Tijuana are no different from those endured by migrants who have crossed the border to live in the United States.

In fact, most people living near the border in Mexico have no hope or expectation of crossing it. More than half of the border residents have no tourist visas or border-crossing cards. Instead they seek a way to earn a living and raise a family where they are. When the wages are low and the housing poor, they try to confront those conditions by changing them, not by crossing over to the other side.

The border has therefore been the scene of some of Mexico’s sharpest social struggles, and the photographs in this collection are an effort to document that social history. This upsurge is not new-it’s been going on for more than a hundred years. For three decades I’ve taken photographs of workers’ efforts to organize to resist the poverty that the border factory regime imposes, showing both the actions in the streets and the cost visible in the homes of workers, miners, and other people living throughout the border region.

The border is a vast area with a vibrant social history. We need to see behind the superficial media coverage of the wall and people’s efforts to get past it. The purpose of my photography in the border region is to provide a broader view historically, to make the invisible visible. The images have a sharp critical edge and are intended to provoke questions about the reality people experience living there.

Maclovio Rojas, on the eastern edge of Tijuana, is home to 1,300 people. It is a community in resistance, first settled in 1988 by people who could find no other place to live in the rapidly expanding city. The land they settled on was unoccupied and belonged to the federal government. Under the old agrarian reform law, people were entitled to settle here and petition the government for formal ownership. Along the dirt roads that fan out like a grid from the highway, peoples’ houses are made of old pallets, unfolded corrugated shipping cartons, and other castoffs from the factories. The community sits on a dry, flat, sandy lowland surrounded by treeless hills.

The land here doesn’t seem very desirable, but on the other side of a dirt road at the edge of town looms the maquiladora of the Hyundai Corporation, and just over the hill is the Florido Industrial Park. The North American Free Trade Agreement and a devalued peso inspired a building boom in Tijuana, and in a few decades a small, honky-tonk tourist town became home to hundreds of maquiladoras.

The growth of the maquiladora industry transformed life for 2 million people who today live in the city. “Tijuana was created this way,” explained Eduardo Badillo, general secretary of the Border Workers’ Regional Support Committee, a community organization active in the city’s barrios. “The government calls these settlements ‘invasions,’ and we call them ‘possessions.’ Whatever you call them, the law recognized our right to build homes on this land, because under the Constitution, it’s our country.”

Land reform rights were weakened, however, by NAFTA-era changes to Mexico’s constitution designed to make it easier for corporations like Hyundai to own land and protect their titles. After building their homes, the Yorbas, Tijuana’s original landowners before the Revolution, claimed that the land was theirs. Residents viewed this as a thinly disguised means for Hyundai to gain possession. The family accused the community leader Hortensia Hernandez of illegally taking their land, and in 1995 she was arrested.

Residents refused to abandon their homes, and the conflict grew. After five months in prison, the family couldn’t come up with documents proving their title, and Hernandez was finally released. When she walked out of prison, she owed her freedom in large part to the Tijuana-based Border Workers Regional Support Committee and the San Diego-based Support Committee for Maquiladora Workers. Both groups helped organize a march from Tijuana to the state capital in Mexicali to demand her release.

Maclovio Rojas became one of many communities like it along the border. Because they were created by land occupations by poor people, often workers from the maquiladoras, the communities’ legal titles were almost always denied by governments anxious to protect investors. Facing efforts to drive them from their homes and off the land, they quickly became communities of resistance. Some were driven away, but others hung on despite the imprisonment of leaders and conflicts with police and golpeadores (thugs who beat people.)

In the 1990s Maclovio Rojas was the scene of conflict like this, but today it is a much more peaceful place, and its residents over the years have forced local government to provide schools and a minimum level of services. The tradition of land occupation is still very much alive, however, and similar communities of resistance exist on the outskirts of almost every large city on the border.

Cañon Buenavista is another community in resistance, created in two separate land invasions by rural workers from the ranches of Maneadero, the agricultural valley just south of Ensenada. The first was led by Benito García, a controversial figure among Oaxacan migrants. He was a charismatic leader of agricultural strikes in the early 1980s, later accused of misusing his authority. In the 1980s Garcia organized farmworkers in the Maneadero Valley who were living in labor camps or even sleeping by the roadside to occupy 50 hectares on a desert hillside south of town. The state government then bought out the people who claimed ownership of the land, and resold it to the occupiers through an agency called the Immobiliaria Estatal.

Julio Sandoval arrived in Cañon Buenavista in 1990 and built a home there for his family. He had already led a similar movement in the San Quintín Valley of Baja California to organize a community of Triqui farmworkers called Nuevo San Juan Copala. The Confederación Independiente de Obreros Agrícolas y Campesinos, a radical rural organization founded by the Mexican Communist Party, led many of these fights, and its leader, Beatriz Chavez, was imprisoned for occupying land for homes.

Sandoval got into trouble with the state authorities when he began telling Cañon Buenavista residents not to make payments on their lots. Immobiliaria Estatal had raised the sale price and payments for each lot, and many families never got out of debt. But Sandoval had discovered that in 1973 the federal government had declared tens of thousands of hectares in northern Baja, including the land Cañon Buenavista sits on, government property. As a result of a new land invasion, Cañon Buenavista’s total population grew to 2,700 families -about 10,000 people, most of whom come from Mixtec and Triqui towns in Oaxaca. Sandoval, however, was accused of taking land by force and jailed in the state prison in Ensenada for two years.

These are communities created by land hunger – people drawn to the border for work but with no provision for housing. To survive, many communities of resistance appealed for support from the Coalition for Justice in the Maquiladoras and other cross-border groups. The Frente Indígena de Organizaciones Binacionales also organized support for indigenous migrants, both in their towns of origin in Oaxaca, in the towns south of the border in Baja California, and in indigenous communities north of the border in California.

At the other end of the border, near the city of Matamoros, maquiladora workers built the settlements of Derechos Humanos and Fuerza y Unidad. Outside of Nuevo Laredo, across the border from Texas, Blanca Navidad, like Cañon Buenavista, also linked itself to the movement for autonomous communities developed by the Zapatistas in Chiapas.

After successfully resisting eviction by the state government of Tamaulipas in 2006, the autonomous indigenous communities of Chiapas sent 1,000 boxes of groceries to the people of Blanca Navidad in support of their north-south alliance. A year later the Zapatista Comandantes Eucaria, Miriam, and Zebedeo held a two-week exchange there and the community built a health center it called El Otro Caracol (The Other Snail). In that meeting Comandante Eucaria explained that women are critical to the survival of communities of resistance:

“As women, we are needed the most in the autonomous town. We start up projects like embroidering work, raising chickens, baking bread. Although we make very little money, we use it for the needs of our struggle, and if any is left over we invest it in mills for grinding masa. That way women will have more time to do other work. We make the decisions and no one can give us orders.”

Figure 1. Maclovio Rojas, Tijuana, Baja California, 1996. The flag of the CIOAC flying at a gate into the community. On the other side of the road and fence are trailers manufactured in the Hyundai factory. Maclovio Rojas residents believed that the state government was trying to drive them off their land so that the industrial park could expand.

Figure 2. Maclovio Rojas, Tijuana, Baja California, 1996. A sign at the entrance into Maclovio Rojas declaring it a civil organization and union of small landholders affiliated with the CIOAC. The CIOAC was organized by the Mexican Communist Party and other leftist activists to help small farmers and the rural poor defend their rights to land. By 1996 the original PCM no longer existed, but in Baja California its activists continued to help migrant workers organize, settle, and build homes.

Figure 3. Maclovio Rojas, Tijuana, Baja California, 1996. Children playing with tires and milk crates in the dirt street.

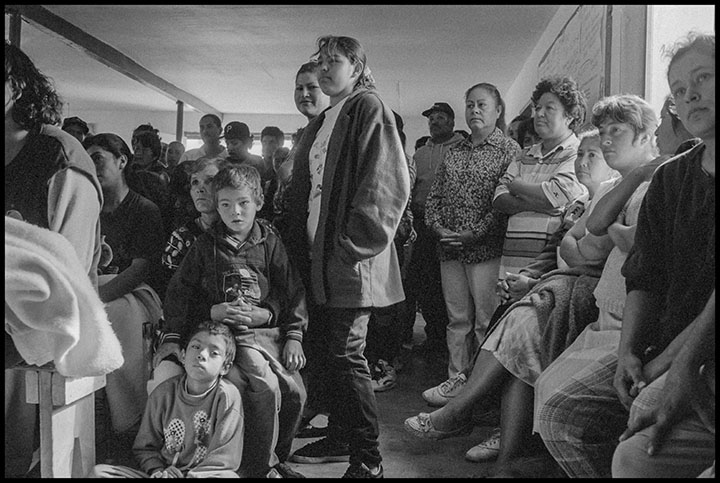

Figure 4. Maclovio Rojas, Tijuana, Baja California, 1996. Residents listening to Hortensia Hernandez speak after she was released from prison, where she had been held for leading the struggle to gain their land rights. “I’ve lived in Tijuana for 21 years, and 9 years here in Maclovio Rojas,” she told them. “We’re fighting to keep our 197 hectares. This is an industrial zone. They’ve told us that they’ve committed this area to transnational corporations. The freeway is going to come through here, so the land has become very valuable. But we’re not going to cede one centimeter.

“The state government wanted to gain possession of the land, but when they saw that we weren’t going to give it up they began to fabricate accusations against us, especially despojo de instigación [provoking an illegal occupation]. Here in Baja California, when they accuse you of this, there’s no bail, but we were able to prove that we were innocent and that the accusations had been fabricated. We showed that these were federal lands, and I was released. The state government sees that they can’t do much to us because of the resistance we’ve put up.

“I was in jail for five months. In the penitentiary a day felt like a year. This prison is a place of perdition. The people held there, instead of being rehabilitated, leave in a much worse state, in which they’ve deteriorated morally and physically.

“People here are poor and often don’t even have anything to eat. With no support from the government to make this land productive, people have to work in the maquiladoras to survive. Over half the people in Maclovio Rojas are workers in various factories. Many work at Hyundai. When some were unjustly fired from the Laymex factory they decided to organize a strike. We went to support them-one of the reasons I was detained.”

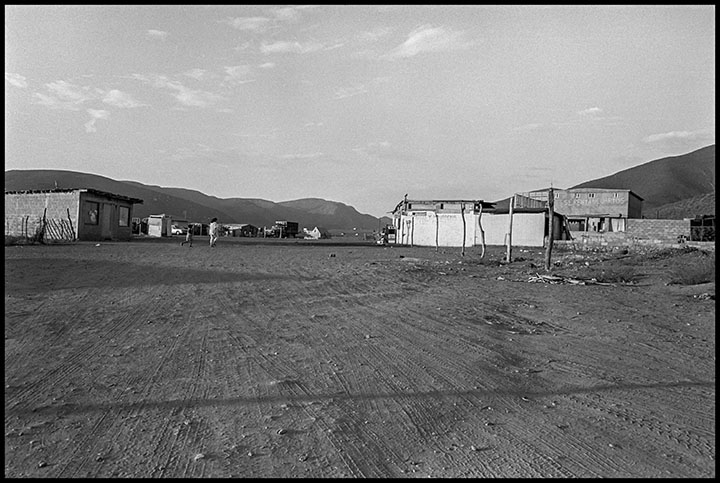

Figure 5. Cañon Buenavista, Baja California, 2002. The town merging into the surrounding desert hills.

Figure 6. Cañon Buenavista, Baja California, 2002. Esther Murillo, a member of one of the 20 families that first occupied 78 hectares in the hills surrounding Cañon Buenavista. They chose May 1, the international workers’ holiday, as the day for their action. “There were only 30 of us at first, and the police surrounded us,” she remembered. “They said they were going to burn the houses we built, but 20 of us stayed up and watched all night. We had our children inside, and we were afraid of what might happen to them. But we were all calm and wouldn’t move, so there were no physical confrontations. At first there were 40 houses, a week later 50. Now there are about 500. But for a long time the police kept coming every night to scare us.”

Murillo had no money to pay rent or buy land. Making 50-70 pesos (US$5-7) a day in the fields and working only during the harvest season, she couldn’t survive. “We’re poor. So what were we going to do?” she asks. Once they occupied the land, however, she and her fellow residents were in for a surprise. “This was just a hillside covered with weeds, full of snakes and tarantulas, and we cleaned it all up, but then, after we’d done the work, a lot of supposed owners suddenly appeared.”

Figure 7. Cañon Buenavista, Baja California. 2002. Juana Sandoval, the wife of imprisoned community leader Julio Sandoval, heating tortillas on a stove set up on cinder blocks and connected by a rubber hose to a big propane bottle that the family has to fill twice a month. Their one large room is dim even at midday, but their home is better than many in Cañon Buenavista. “Some of us live in cardboard houses and cook on wood fires, a very dangerous combination,” Julio said in a phone interview from prison. An exterior plywood wall was charred in one such fire, which burned down the home next door.

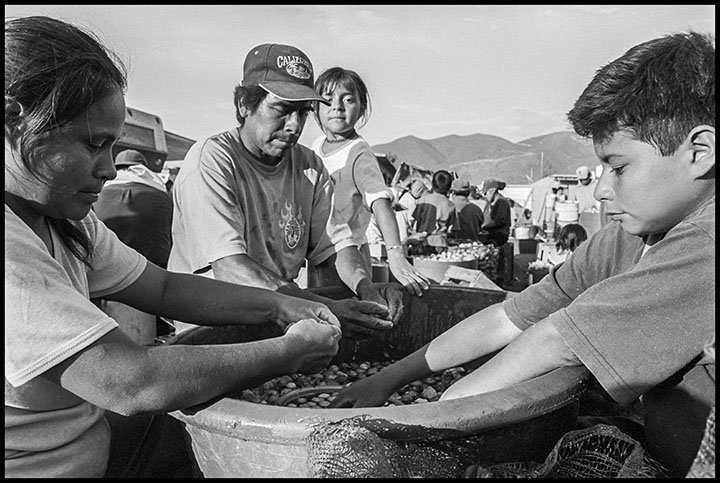

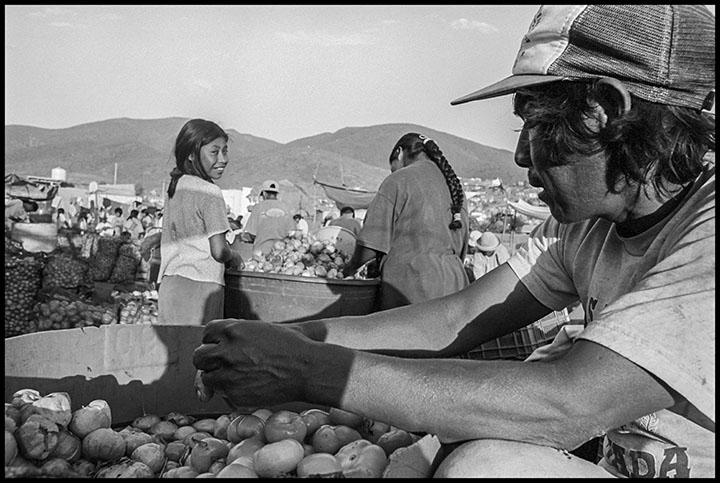

Figure 8. Cañon Buenavista, Baja California, 2002. Residents husking tomatillos for very low pay from the big Herdez canning plant in Ensenada.

Figure 9. Cañon Buenavista, Baja California, 2002. Residents talking and joking to make the time pass while they work husking tomatillos.

Figure 10. Blanca Navidad, Tamaulipas, 2006. Community leader Blanca Enriquez working in the community garden. Before building the garden and a community health center, she said, “We had nothing. When the government tried to evict us all we had left were tarps and poles, and a few blankets. The majority of us in this colonia work in the maquiladoras, but regardless of where we work we are from this community, and we all are equal.”

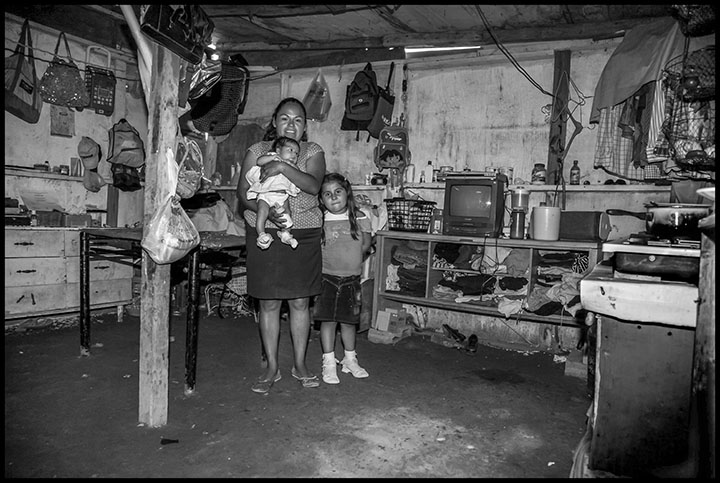

Figure 11. Blanca Navidad, Tamaulipas, 2006. A family inside its home, which has a dirt floor and plywood walls salvaged from construction in the factories. Colonias like Blanca Navidad have been called “lost cities”-places, according to the journalist Javier Hernández Alpízar, “where excluded Mexicans live, stripped of their right to housing.” In acute contrast, not far from the colonia is the bridge crossing the border to the United States known as the World Trade International Bridge.

Figure 12. Blanca Navidad, Tamaulipas, 2006. The extended family of a maquiladora worker. In 2006 the people of the Blanca Navidad community were brutally evicted when Nuevo Laredo’s mayor sent in tractors to demolish their houses; many houses were burned, leaving women and children with nothing. When El Mañana exposed the local government and supported the community in its struggle for its land, the newspaper office was bombed and a reporter was seriously injured. Those responsible for the bombing were never identified.

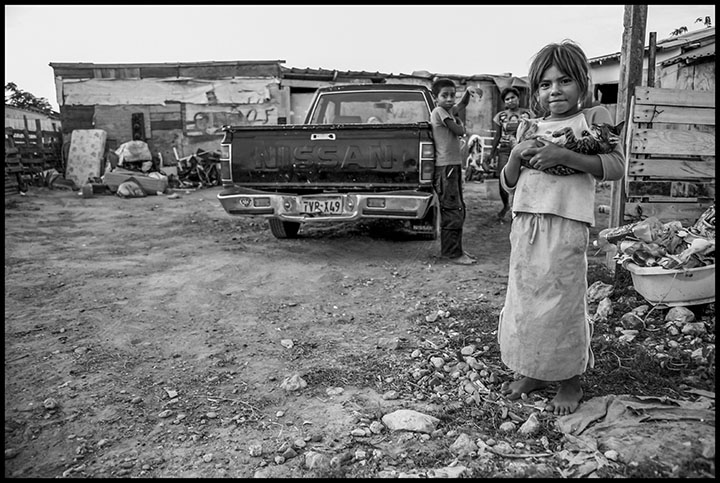

Figure 13. Blanca Navidad, Tamaulipas, 2006. A little girl holding her pet cat in front of her house.

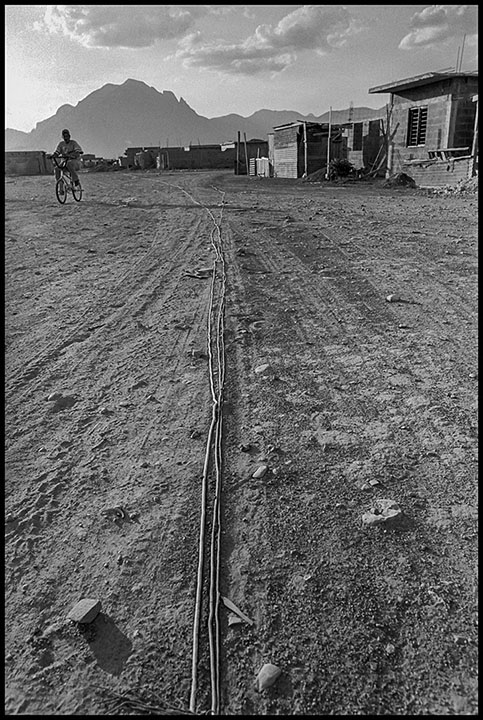

Figure 14. La Alianza, Nuevo León, 2001. Electric wires illegally hooked up to the main line half a mile away snaking into the barrio of La Alianza. The city of Monterrey provides no services to many barrios of maquiladora workers like this one while providing investment and support to developers of the industrial parks where the workers are employed.

Figure 15. La Alianza, Nuevo León, 2001. A woman leaning on her shovel in front of her home, the walls of which have been assembled out of metal plates, bedsprings, and salvaged wood.

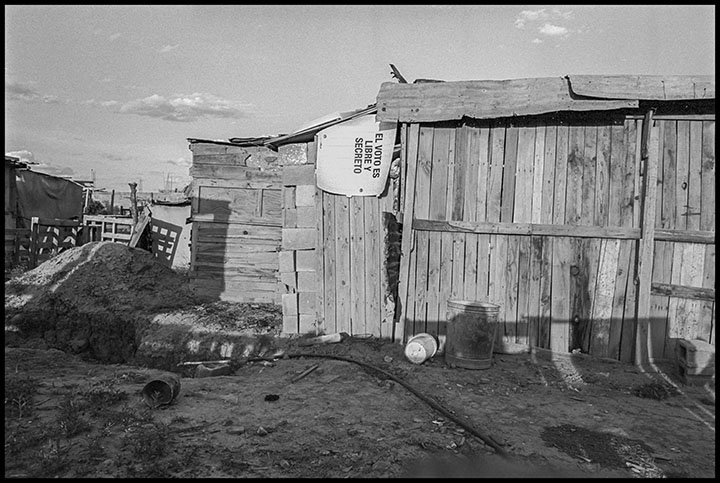

Figure 16. La Alianza, Nuevo León, 2001. A placard from a recent election reading “The vote is free and secret.” One of the strongest defenders of the residents of La Alianza and of poor barrio residents in Monterrey generally was Ignacio Zapata, who challenged fraudulent elections that kept the parties of poor and working-class people out of power.

Zapata helped found organizations like the Alliance of the Users of Public Services, which fought for electricity, water, and municipal services in La Alianza and other barrios, and the Binational Pro-Bracero Alliance, which fought to recover the money taken from the pay of bracero migrants in the United States from the 1940s to the early 1960s.

Originally a believer in liberation theology, he joined the Mexican Communist Party, later helped organize the Mexican Socialist Party (the precursor of the Party of the Democratic Revolution), and supported the 2006 presidential campaign of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who was elected President of Mexico as the candidate of the Movimiento Regeneracion Nacional in 2018.

Figure 17. Derechos Humanos, Tamaulipas, 2006. Buses waiting to take residents of Derechos Humanos and Fuerza y Libertad to the factories where many work and to the bridge where they cross the Rio Grande to Brownsville, Texas.

Figure 18. Derechos Humanos, Tamaulipas, 2006. A small business run from home, selling buns, chocobananas, and tostada snacks.

Figure 19. Derechos Humanos, Tamaulipas, 2006. A boy jumping across a rickety bridge over a polluted canal near the U.S. border. The canal, which is contaminated by toxic chemicals dumped by the factories, runs alongside homes. Residents built the bridge to get from one part of the neighborhood to another.

Figure 20. Derechos Humanos, Tamaulipas, 2006. A boy bringing home wood for the stove.

Figure 21. San Francisco, California, 2016. Elvia Villescas, the director of Las Hormigas, a community organizing project in a neighborhood of Ciudad Juárez where many maquiladora workers live. She describes her community as follows:

“We’re located in Anapra and Lomas de Poleo, very marginalized communities in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, on the U.S. border. We began Las Hormigas to organize educational and human development projects. Anapra and Lomas de Poleo became famous because of the number of women’s bodies found there during the feminicides. In both neighborhoods there are many families that had lost a daughter or a sister who disappeared or was murdered.

“Anapra is a community that has been abandoned. On the surface it looks developed. It’s on a big highway, and big trucks go by all the time to the border crossing. There are some big businesses along the highway because the government has opened this commercial space for them, but if you walk just one or two blocks into the neighborhood you’ll see very deep poverty.

“Anapra has about 20,000 inhabitants. People living there have big health problems because the sanitation is so bad. Many homes still have no sewers or drains, so the wastewater runs into the streets. The government hasn’t invested money in the schools. So in that sense, there is a lot of repression against this community.

“The majority of the people living there are migrants, and a great number work in the maquiladoras. In Las Hormigas we’ve done mini-surveys during our workshops, asking people to raise their hands if they work in a maquila. Out of 30 people, 10 or 12 will raise their hands. So imagine that in Anapra 30 or 40 percent of the people living there work in a maquila. There’s a great need in this community for education-not schoolbook education but education in rights and solidarity.

“The media refuse to carry stories about this movement [the Juarez strikes of 2015] in the four maquiladoras or treat it with the importance it deserves. In Commscope 178 workers were fired, and there are four maquilas where this has happened, but people have little information about this. Those who do know about it don’t want to talk because they’re afraid that if they say anything they’ll be identified as troublemakers and the companies will start watching them.

“There is a list of workers whom the companies are watching and following. There are threats all the time that if you do something they don’t like, you’ll never get a job in a maquiladora. Workers in the maquilas are always very afraid that anything they say may lead to losing their jobs, and a maquila job is still seen as a job with some security-very poorly paid but at least you’re working.

“The workers are producing all the wealth but receive very little benefit from it, while the companies make a lot of money. The maquiladoras will not permit workers to organize unions. To allow that would mean that they would have listen to them and respect their labor and health rights. The maquiladoras have no conscience, no sense that workers have rights. They comply with the minimum that the law demands, but there’s no sense that because they have thousands of workers they should give them better wages or a clinic or a child care center for the women workers.

“People are tired of the wages. At 170 pesos a day you can’t buy anything. You go to the store and buy three or four things and you’ve spent 500 pesos. But I think that in Mexico generally there is also an exhaustion that has grown and grown. People have grown tired of seeing so many abuses tolerated by those who are on top, whether it’s a maquiladora or the authorities. The demand is growing that they begin to respect people’s rights. This process has developed over a long time, and we’re reaching the limit. That’s important, because for so many years we’ve been living with everything.

“This movement of people in the maquilas is very important. We have to know about it and support it. It is the power of unity against the economic power. It’s something incredible. A union with power here would make a very big difference. It would give power to the people, to the workers. Instead of just working to earn their 800 pesos people would feel that they have the ability to make decisions, to demand what they need. Right now, if you are a worker and if you need someone to take care of your child, that means nothing to the maquiladora. You say, ‘I need someone to take care of my baby,’ but the maquiladora doesn’t hear your voice. But if there’s a union with the strength that comes from unity the maquiladora will have to listen.

“I love my country, but sometimes it gives me great pain. We need to wake up and recover who we are. We have to change the direction everything is going, all the corruption. It’s a very important moment. This movement of maquiladora workers is taking the leap, making us question who we are. It’s a very positive signal that things may be difficult but we are going to see a change.”

Leave a Reply